It was here that I first remember an interest in living things. Wandering under a searing blue sky along the beach you might find large horseshoe crabs, living fossil survivors from the Ordovician 450 million years ago. If the tide was out, there would be mudskippers ogling you with their bulging eyes, before skipping away to safety. Above all, there was the shell mountain at the nearby lime works. You could climb – crunch, crunch – this schoolboy collector’s dream and never tire of finding the next most beautiful seashell, only to discard it for an even more precious one.

Posted back to Germany, the first years in the comprehensive BFES Kent School were marred by bullying, an inevitable consequence of being an outsider who actually liked to learn. I also spent some time in the German education system, which by contrast was competitive and results driven, and challenging in a different way.

Lacking Latin, I could not advance to a higher German school after achieving the German ‘O’ level equivalent. Instead, I went to a Waldorf School, based on the anthroposophical principles of Rudolf Steiner. A great and holistic experience. Once scared of maths, I learnt trigonometry here without difficulty. We spent a week mapping one of the small North Frisian Halligen islands. There, in the evenings, we sat in a circle, reading out or telling ghost stories as there was no TV or radio in the youth hostel where we slept. It was said that in times of storms and high tides, the people on one island would pray that the dykes on neighbouring Halligen would fail, so the sea level would drop and their island would be spared flooding.

I returned to forces education at BFES Queen’s School, Rheindahlen, to do my ‘A’ levels in the three sciences. Those years attracted a more eclectic group of students with, for some reason, a fascination and enjoyment of the Goon Show. We promptly renamed ourselves and one class had three Neddy Seagoons, differentiated as Mk I, Mk II etc.

We had an enthusiastic Welsh biology teacher with the slight impediment that the sight of blood made him faint. We only discovered in a practical on blood group testing. My friend (Neddy Mk I) pricked his finger and only then remembered that he was a haemophiliac. All the while he produced a gentle but steady stream of blood drops. Desperately trying not to faint, our teacher had to tell us what to do from a distance.

The decision loomed on what to do next, after my ‘A’ Levels. I found myself trying to choose universities in a country that I had not lived in since the age of two. Our biology teacher was so enthusiastic about ‘The Mountains, the Sea and the Daffodils’ that I put down Aberystwyth as one of my choices.

Coming to live in the UK, and Wales in particular, was a bit of a culture shock. Apparently, the world was not divided into Officers & kin and Lower Ranks & kin (to which I belonged). There were apparently still strong tribal groupings known as the English, Scots, Irish and of course, the Welsh. In 1976, I had landed in Aberystwyth on the border between North and South Wales – Diolch Yn Fawr! It was said that you either loved or hated the place as a student and that a good 30% departed during the bleak winter days.

I loved Aberystwyth. When not studying, you could go down the hill to the windswept promenade. On really stormy days, the crashing waves would break upon the sea wall and throw pebbles over the top of the three storey Alexandra Hall into the street behind. On calm days, you could wander along the cliffs. A good friend David, a mature law student from Blaenau Ffestiniog, introduced me to the Welsh hills and the graveyards where his stonemason father and grandfather had work on display. Having learnt the art of working stone by hand too, he would proudly comment with a grin, “I helped on that one”.

My knowledge of Britain grew gradually. I began with a line from Dover to London to Birmingham to Shrewsbury to Aberystwyth – the route to and from Aber’ from Germany. Over time, new places were then mentally slotted in – north or south of the line.

Time flew. In the final year I met my future wife, Jane, and also had to come to a decision on what to do next. I enjoyed researching for my Biology degree final year and began looking around for possible PhD studentships. In 1979, an Aberystwyth offer came through first, so I reluctantly forewent the opportunity of a Zoology PhD and living in the red-light district of Southampton (where the cheapest student digs were, apparently).

Professor Mike Hall ran a group researching plant hormones, in particular, ethylene. Ethylene (a gas) is the hormone plants use to stimulate DEATH. A bit drastic you might think, but very important. For example, a row of cells at the base of a leaf is programmed to DIE to help the leaf cut itself off from the rest of the tree and fall in autumn.

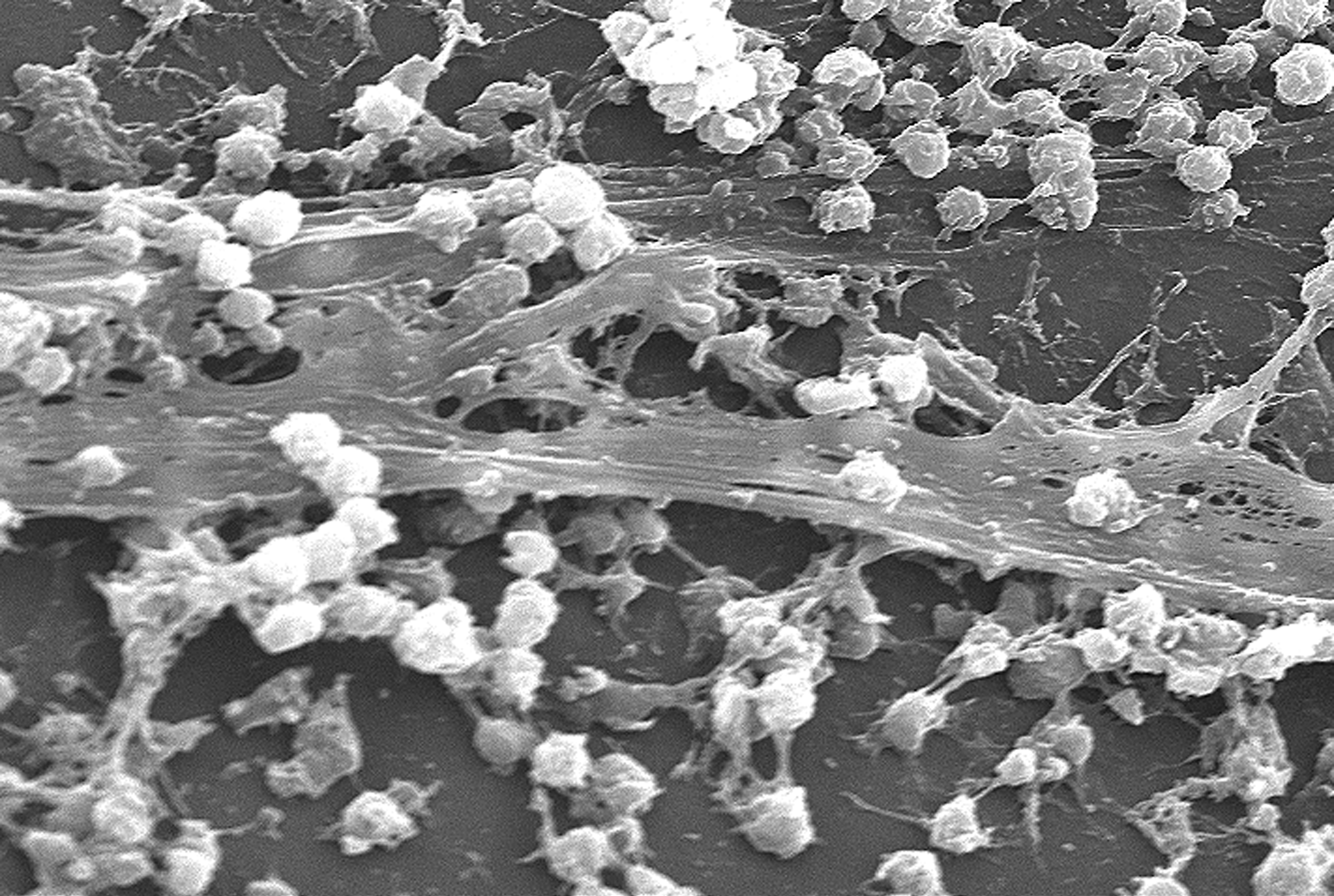

Science at the time thought, that if there is a hormone, there has to be a receptor molecule within the plant to which the hormone binds. I was part of a team trying to characterise and isolate this ethylene receptor. My first important lesson was to learn about beans and bean plants. Beans bind ethylene. If you want to know if a plant is a bean plant – I’m the man to ask. (Ethylene also ripens fruit. I can now safely identify a banana).

By the end of my PhD, I had convincingly described an elongated molecule that bound ethylene. The next PhD generation could take up the reins.

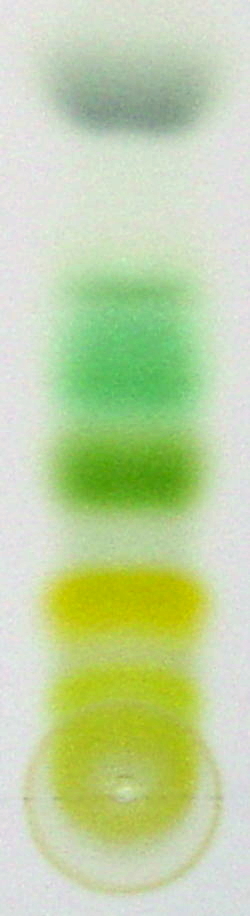

My first postdoc position was at the former National Vegetable Research Station in Wellesbourne, near Stratford upon Avon. Here I worked on bigger molecules, plant viruses, as part of a team run by Dr Ron Fraser.

This was the dawn of genetic engineering in plants. Our aim was to isolate and sequence the DNA of a particular plant virus; one that actually made plants resistant to serious virus attack. We were pipped to the post by researchers at the John Innes Centre if I remember correctly. However, in addition to bean plants (and bananas), I could now identify tobacco and tomato plants.

The experience did win me a permanent post at Twyford Plant Laboratories (TPL), in Somerset. I joined a team as a Senior Research Scientist looking at different ways to make plants resistant to viruses. Jane and I lived under the shadow of Glastonbury Tor and possibly on a ley-line. One of my memories is cycling to work across snowy country lanes, having to stop every 20 metres or so to remove the snow that had clogged up the wheels to immobility.

TPL was a commercial company and I successfully survived two cycles of redundancy before joining the part of the company that was bought out and transplanted to Cambridge. At the new opening we asked our new owners why they had bought us. “Well, it was either buy you or pay for a week’s advertising campaign in a major newspaper!” That put us in our place.

I worked on a number of projects, the most important of which was trying to make potatoes resistant to potato cyst nematodes – a century old epidemic still haunting our fields. My team collaborated with Leeds and York Universities. The company ran GM trials, so we had days out of the lab planting potatoes in cold April mud and harvesting under searing summer sun. I now know a potato plant too when I see one!

At the end of 2003, the parent company decided to direct its efforts elsewhere and I was part of redundancy round III, after 20 years in research. In a sense it was a relief. I enjoyed the lab work, but now it was all project management, whilst others did the fun lab stuff.

I had learnt all about DNA, cloning and sequencing, GMOs etc. I could now identify beans, tomatoes, tobacco, potatoes and Arabidopsis (a weed important in plant science) and of course, bananas.

What could I do next?

Time for something totally different! I set up my own company, Milton Contact Ltd. My aim: To help UK businesses enter the German Market, using my intercultural skills.

Now – I run a publishing company, but that’s another story!

What would I say to others wanting to set up their own business?

If you are thinking about setting up your own business, do your research, seek advice and Go For It! If you don’t try you can’t succeed.

There are many free or low-cost courses for business start-ups. It’s a good way to learn and meet others in the same boat.

I would also recommend you look around for a friendly business network. The support, information and experience that is shared is invaluable – and you make good friends too. I’ve been a member of the Huntingdonshire Business Network (HBN) for 12 years.

What's Chris doing now?

Chris is Director of Milton Contact Ltd and says: We turn your dream of a book into a reality. Reading your manuscript for the first time is always exciting. We do so in confidence and give you constructive feedback on its strengths, offering suggestions to make it even better where appropriate.

You can have as much or as little help as you want. Together, we format and set your text and pictures, and offer advice on book size, font designs and choice of colour or monochrome. We can add flourishes such as drop- or illuminated capitals and additional artwork. We also design book covers and can help you with the all-important teaser text on the back of the book. We then find a suitable and cost-effective printer for you. Alternatively, we can create an e-book.

The book is registered through its ISBN and 6 archival copies are deposited with the British Library and the Agency for the Legal Deposit Libraries. All income from book sales is yours. You retain the book content copyright.

Go for it contains 16 stories that show, whatever your beginnings, you always have the choice to follow a new path.

Whether you are in business yourself, a new start-up, thinking of changing your job, or a school leaver taking the first steps into work, we hope this book will encourage you to build YOUR new future: Go For It!

For more information or to order a physical paperback copy, please contact: Chris@miltoncontact.com. Alternatively, you can get the Kindle version here:

https://goo.gl/8P9Oqu.